Contents:

Monocotyledons

Dicotyledons

Monocotyledons

Cotyledon means natural leaf borne of a seed of a plant, it is also known as seed leaf.

Monocotyledons also are known as monocots are plants with only one cotyledon or seed leaf. Examples are cereals like maize, sorghum, wheat, millet, barley, and grasses etc.

Features

They possess one seed leaf, fibrous root system, parallel aeration, long and narrow leaf, non scented dull flower etc.

Dicotyledons

The dicotyledons, also known as dicots, is one of the two groups into which all the flowering plants or angiosperms were formerly divided. The name refers to one of the typical characteristics of the group, that is, the seed typically has two embryonic leaves or cotyledons. There are about 200,000 species within this group. Examples are legumes such as cowpea, groundnut tree, cocoa, fruit crops – orange, guava, vegetables – tomatoes and pepper.

Features

Dicotyledons plants have two seed leaves, tap root system, leaf stalk or petiole, epigeal germination, colorful scented flowers.

Monocot and Dicot

Differences between Monocotyledons and Dicotyledons

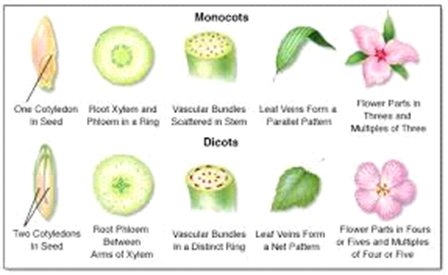

| MONOCOTS | DICOTS |

| Embryo with a single cotyledon | Embryo with two cotyledons |

| Pollen with single furrow or pore | Pollen with three furrows or pores |

| Flower parts in multiples of three | Flower parts in multiples of four or five |

| Major leaf veins parallel | Major leaf veins reticulated |

| Stem vascular bundles scattered | Stem vascular bundles in a ring |

| Roots are adventitious | Roots develop from radicle |

| Secondary growth absent | Secondary growth often present |

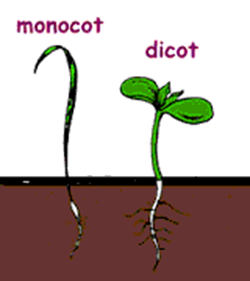

Number of cotyledons — The number of cotyledons found in the embryo is the actual basis for distinguishing the two classes of angiosperms and is the source of the names Monocotyledonae (“one cotyledon”) and Dicotyledonae (“two cotyledons”). The cotyledons are the “seed leaves” produced by the embryo. They serve to absorb nutrients packaged in the seed until the seedling is able to produce its first true leaves and begin photosynthesis.

Pollen structure — The first angiosperms had pollen with a single furrow or pore through the outer layer (monosulcate). This feature is retained in the monocots, but most dicots are descended from a plant which developed three furrows or pores in its pollen (triporate).

Number of flower parts — If you count the number of petals, stamens, or other floral parts, you will find that monocot flowers tend to have a number of parts that is divisible by three, usually three or six. Dicot flowers, on the other hand, tend to have parts in multiples of four or five (four, five, ten, etc.). This character is not always reliable, however, and is not easy to use in some flowers with reduced or numerous parts.

Leaf veins — In monocots, there are usually a number of major leaf veins which run parallel the length of the leaf; in dicots, there are usually numerous auxiliary veins which reticulate between the major ones. As with the number of floral parts, this character is not always reliable, as there are many monocots with reticulate venation, notably the aroids and Dioscoreales.

Stem vascular arrangement — Vascular tissue occurs in long strands called vascular bundles. These bundles are arranged within the stem of dicots to form a cylinder, appearing like a ring of spots when you cut across the stem. In monocots, these bundles appear scattered through the stem, with more of the bundles located toward the stem periphery than in the center. This arrangement is unique to monocots and some of their closest relatives among the dicots.

Root development — In most dicots (and in most seed plants) the root develops from the lower end of the embryo, from a region known as the radicle. The radicle gives rise to an apical meristem which continues to produce root tissue for much of the plant’s life. By contrast, the radicle aborts in monocots, and new roots arise adventitiously from nodes in the stem. These roots may be called prop roots when they are clustered near the bottom of the stem.

Secondary growth — Most seed plants increase their diameter through secondary growth, producing wood and bark. Monocots (and some dicots) have lost this ability, and so do not produce wood. Some monocots can produce a substitute, however, as in the palms and agaves.